Venizelos Street was constructed during the Ottoman Empire, in 1867-1870 when the seaward section of Thessaloniki’s Walls was demolished.

Sabri Pasha Street, as it was originally named in honor of the reformer “Vali” (Administrator) of the time, connected the “Konak”, the administrative headquarters, with the quay and was about 1.5 km long. The street gradually became the core of the city’s business activities. The newly constructed Eleftherias Square (Plateia Eleftherias), which at that time was smaller in size and was named Olympus Square, gave the chance to dozens of businesses to operate at the area. A large number of retail stores and businesses belonged to Jewish merchants.

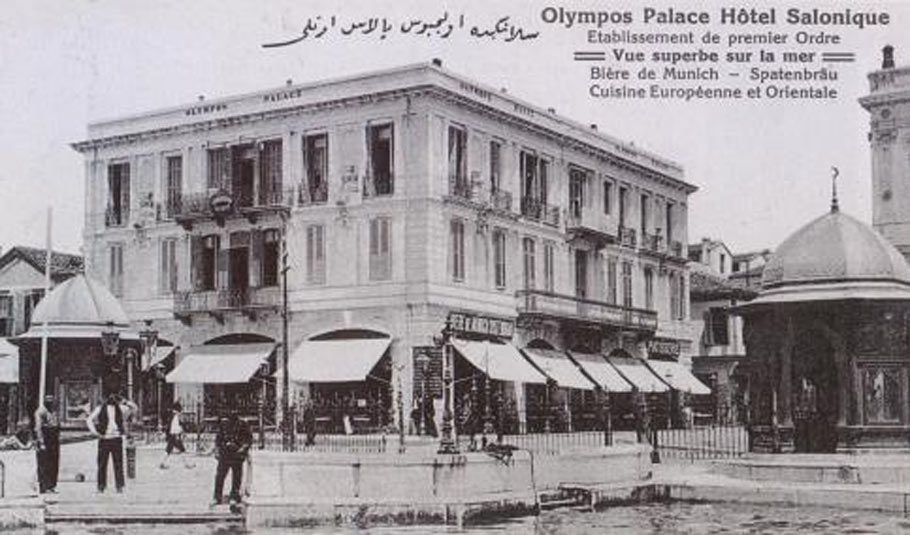

The beginning of Venizelos Street at the port

With Olympus Hotel and the homonymous brewery at its ground floor at the beginning of Venizelos Street, before the widening of Eleftherias Square, with Stein building and its distinctive globe, this section of Venizelos, below Tsimiski Street towards the quay became the cosmopolitan centre of Thessaloniki.

View of Olympus Hotel from the sea.

The street was renamed after Eleftherios Venizelos, Prime Minister of Greece, when the city was liberated in 1912 and the new territories in the northern part were annexed to Greece. The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 destructed completely a big part of the buildings at the center of Thessaloniki, including Olympus Hotel. According to the new city’s plan Eleftherias Square got bigger and Venizelos Street prevailed as the city’s business landmark.

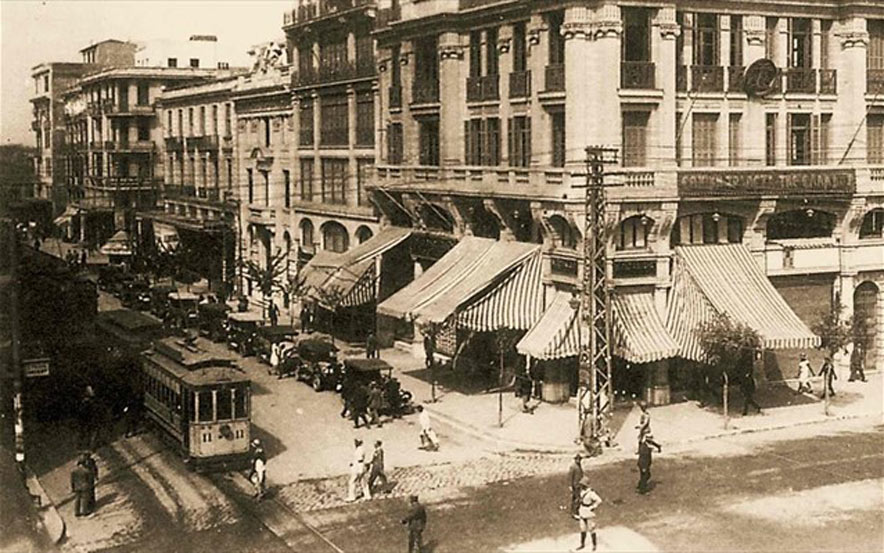

The tram passing along Venizelos street at its corner with Tsimiski Street

The interwar period

The redesigned city’s urban plan that occurred after the fire of 1917 gave Venizelos Street and its vicinity a primarily business character with the construction of buildings that housed stores, office and craft spaces.

Venizelos came up to be one of the priciest commercial streets after the auction of the new land plots that followed the application of Hebrard’s city plan.

Although the fire led thousands of Jews to evacuate the Thessaloniki’s center, Jewish businessmen and the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki bid away almost half of the new land plots.

According to a relevant research project conducted by the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki several buildings belonged to Jews during the interwar period (http://www.salonikajewisharchitecture.com/).

Despite their longtime presence at the commercial heart of the city, Jews were gradually losing ground in the financial sector to Greek Christian businessmen. Jewish entrepreneurship was directly affected by a series of discriminating measures such as the enforcement of Sunday holiday all over Greece, while Saturday (Sabbatyh) is the day of rest and pray for the Jews.

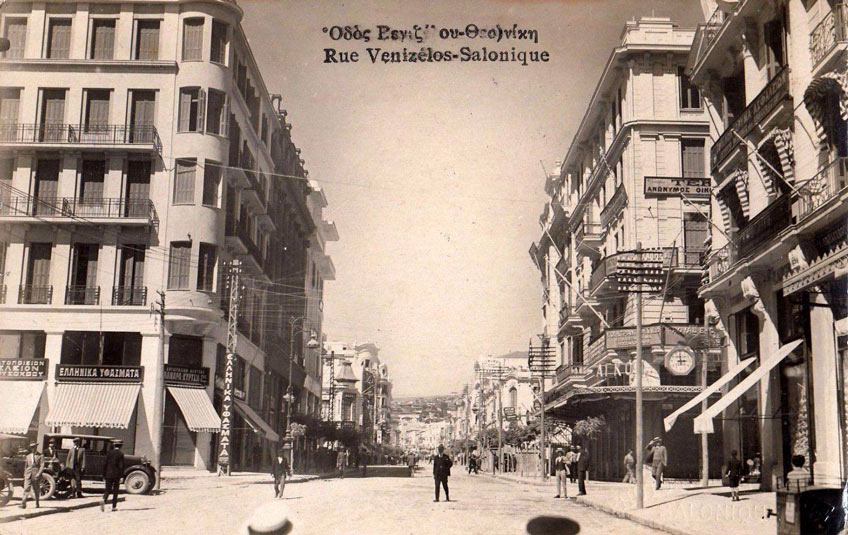

Panoramic view of Tsimiskis and Venizelos Streets with the tram turning into Agiou Mina Street

In 1936, after Ioannis Metaxas imposed the 4th of August dictatorial regime, Venizelos Street was renamed Vasileos Konstantinou (King Constantine). The street continued to be referred as such during the Second World War and the occupation by the Germans.

In 1943, the Service for the Disposal of Jewish Properties (YDIP) included Venizelos Street as Vasileos Konstantinou, during the registration of Jewish properties, stores, offices and houses.

The Greek collaborationist regime set up YDIP by order of the Germans. YDIP was an expedient tool for the expropriation of Jewish properties.

Venizelos Street during the interwar period

After the war

In 1945, after the end of the war, the City Council of Thessaloniki decided to rename the street Venizelos, as it is still named today.

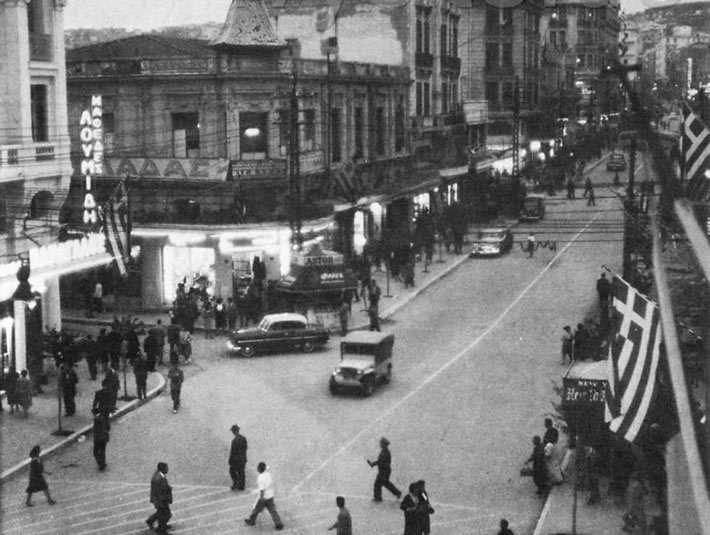

Corner of Venizelos and Agiou Mina streets in 1957-58. Greek flags are visible.

Thessaloniki was heavily reconstructed after the end of the Second World War and the Greek Civil War. Urbanization and the construction of multistory buildings completely changed the look of the city center. Venizelos St. remained at the epicenter of the city’s commercial life housing commercial blocks along with some distinctive buildings from the interwar period.

Following the 1943 persecution and the Holocaust (Shoah) the Jewish properties and the Jewish presence decreased drastically. Only a few Jewish businessmen are reported after the war.

The intersection of Venizelos St. and Tsimiskis St. after the war

At that time Tsimiski’s traffic moved in the opposite direction from today and Venizelos used to carry two-way traffic.

Venizelos Street as a political point of reference

Beginning with the Greeks who demonstrated claiming Macedonia and the conflict with the Bulgarians Venizelos St. and Olympus Sq. became points of political action. It was after the Young Turks’ Revolution that Olympus Sq. was renamed as Eleftherias Square (Plateia Eleftherias).

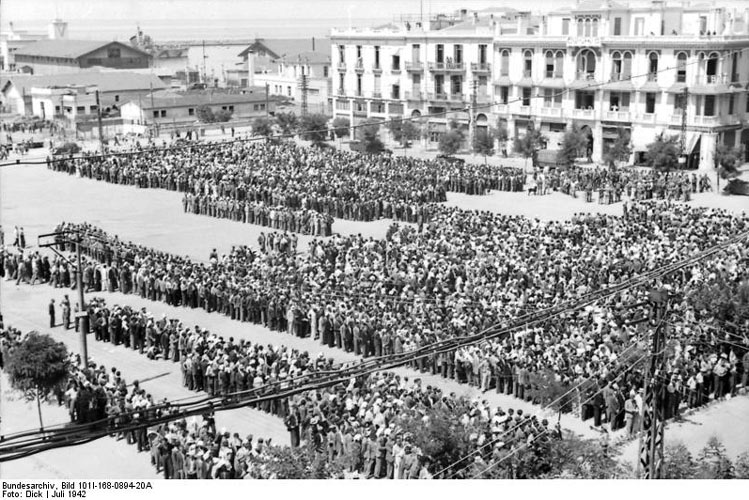

However, the most significant incident that marked Eleftherias Square has been the gathering of all Jewish males (17-45 years old) on Saturday 11th July, 1942 to register for forced labor. Thousands of Greek Jews were mistreated and humiliated by the Germans while they were standing for hours under the sun.

That day was named “Black Sabbath” and was the prelude to the deportation and extinction of the Jewish population of Thessaloniki.

The gathering of Greek Jews in Eleftherias Square in July 1942

Since 2007 Thessaloniki’s Holocaust Memorial stands in the right side (southeastern) of Eleftherias Square, were Nikis and Venizelos streets meet.

Holocaust Memorial, Eleftherias Square

The assassination of Grigoris Lamprakis

The assassination of Grigoris Lamprakis in 1963 revealed how deeply Venizelos St. had changed. A guilty silence covered the killing of the Jews while the Civil War destroyed social cohesion.

Jews were no longer there and in Venizelos St. only a few businesses were left, such as the Kounio photo studio, reminding of the significant Jewish presence of the past.

The Civil War tensions lingered for years and resulted, inter alia, in the assassination of the member of the Greek parliament Grigoris Lamprakis at the intersection of Venizelos and Ermou streets by rightist paramilitaries. Lamprakis participated in a union event for peace. As mentioned, the assassination could only take place in Thessaloniki, which was now a dark city that lost its prewar cosmopolitan character.

A year before, in 1962, during the celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of Thessaloniki, the "Fairy Tale of Thessaloniki" by the writer George Vafopoulos was more or less described as "anti-national" and "treacherous". Vafopoulos mentioned in his text that Ottoman Thessaloniki was characterized as a “Jewish city” because Jews constituted the major ethnic group in the city. Under this pretext the book was considered as insulting the Greek national character of post-war Thessaloniki.

Venizelou street, renamed as King Constantine street (1936-1945), in a detail of Thessaloniki's map of 1943. Historical Centre of Thessalonik